Six years ago today I got my first tattoo. I say first, even though it’s currently the only one. However, many others are planned. I wasn’t ever sure tattoo would be a thing for me, but it turns out it really, really is.

Tattoos have many meanings and connotations, and they can range from very personal to broader cultural assumptions about tattoo and people who choose to wear them. I have Japanese heritage. I am a woman. I am a feminist. These things intertwine in a complex narrative to create what tattoos mean for me.

Please note, this is just my own personal story about what tattoos mean. They will and do mean a lot of other things to a lot of other people.

Tattoo and my illness

The story of my first tattoo is wrapped up in the story of my chronic illness. In 2007 I got sick with a bad flu and never got better. Eventually after two years of telling doctors and specialists I was tired, I got a fuzzy diagnosis of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. It was not a fun time. I failed papers and stressed friendships. I was too tired to draw most of the time, which was like losing part of myself. I couldn’t hold conversations because I’d forget what I was saying halfway through a sentence. Eventually after a lot of trial and error and exhaustion I found a mix of rehabilitation that worked well for me, and undertook a slow path to recovery.

Moving to Wellington was the first major turning point since being diagnosed with CFS. I’d always wanted to live in Wellington, and moving down in October of 2008 felt like a wonderful dream.

I took that moment to get a tattoo, to celebrate the journey I had been on up until this point and to acknowledge the struggles I’d been through to get there. CFS doesn’t leave any scars. I didn’t have anything visible on the outside of me that let myself or others know what I’d been through. A tattoo seemed like the perfect way to give myself a visible marker to point to.

My tattoo is six years old now. The ink is slowly bleeding and fading colour. A part of me wants to get it touched up to improve its shape, but another part of me is happy watching the ink age into my skin. It’s a fixed point in time I’m drifting away from, and I’m really enjoying what that means and how that feels. When I get caught up in everyday things I only have to look down at my wrist and remember the biggest struggle I’ve been through to date, and how I’ve survived it. It’s become a constant comfort, and I’m really happy with that.

Tattoo and Japanese heritage

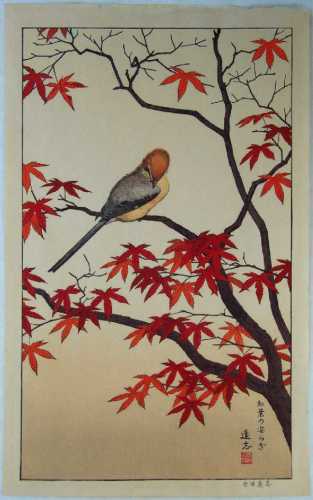

For a long time I have wanted tattoos that celebrate my Japanese heritage. It’s been an internal conflict I’ve struggled with for as long as I’ve wanted them. Tattoo is commonly thought of to be associated with Yakuza in Japanese culture, and if I ever want to live in Japan it’s possible I’d run into problems trying to visit onsen or join a gym because of the negative connotations that tattoos carry.

A part of me that has struggled with celebrating my heritage in a way that my family (specifically my grandmother) would strongly disapprove of, not to mention wider Japanese culture. If I want to get something that celebrates Japanese culture and my heritage, why am I feeling compelled to do it in such an un-Japanese way? I’ve been reading, researching and learning as much as I can about Japan and Japanese culture to decide what to do.

While the popularity and meanings of tattoo have shifted a lot in the last 200 years, tattoo is still an undeniable part of Japanese culture. In that last decade tattoo popularity in Japan is slowly on the rise.

Japan inked: Should the country reclaim its tattoo culture? This article helped me to know a bit more about the history of Japanese tattoo, how it is tied with Kabuki and Ukio-e prints, and that its abolition was linked to crushing a rising merchant class, oppressing the indigenous inhabitants of Okinawa and the Ainu in Hokkaido, especially the leading women of those cultures.

In this context I feel like getting tattoos is a powerful positive statement. It is stepping up and celebrating the parts of a culture I am tied to, while in the same way rebelling against the dominating forces that banned tattoo in the first place. These patriarchal attitudes are not ones I wish to subscribe to, and I don’t wish to let my acknowledgement of my heritage be stifled by their oppression. I fight against these attitudes here in the west, why would I not fight them from a Japanese perspective too?

I know my grandma is going to hate them. When I’ve talked to her about tattoos I want that celebrate my heritage she asks me why I don’t just make clothes with the artwork on to wear, why I want it imprinted in my skin. It makes me sad that I won’t be able to make her understand and she will view them as being ugly. I’m comforted here by the fact that most people’s grandmothers probably don’t like their tattoos, and they still get them anyway. And their grandmas still love them anyway. I’m sure mine will forgive me for making this choice.

As Japanese diaspora my connection and relationship to Japan is different to that of someone who has always lived in the country. Growing up in New Zealand there is the acknowledgement of this culture that I live in and am a part of, and what tattoo means here. I feel like getting tattoos will help me to celebrate and connect these two parts of myself, and help anchor me to my Japanese heritage.

Tattoo and feminism

Go anywhere in the world and talk to almost any person and you will find someone with an opinion about what women should do with their bodies. Women’s bodies are treated as public property. This is why street harassment is culturally accepted the world over. It’s why people have such strong feelings about a woman’s right to choose what happens to her body. It’s why women have to fight to be able to look after their own reproductive health. It extends to people feeling entitled that women should look and dress in a way that they find appealing, right down to their body shape and size.

A tattoo to me symbolises bodily autonomy. It is me saying that I want this on my skin forever, and it is a choice I am making to do so. It is me reclaiming my body in a very direct way. A tattoo isn’t for anyone else to like. It is for me to show you that this is my body and it gets decorated the way that I want, and you have to deal with it.

My feelings about tattoo and bodies and feminism and racism are better summed up by this post from Margaret Cho.

Tattoo and art

I’m a very visual person and always have been. My life is a song of visual images and it’s always been something I want on my skin. I see other people with their tattoos and sleeves and I love the look of the curls of ink wrapping arms and thighs, framing feet and backs and every possible inch of skin that will keep ink in.

My drawings spill out from me onto a page if I’m lucky, but I also see illustrations written into my skin – like if I just scrubbed hard enough the images would come through.

Tattoo is the closest way I can get to this feeling. And as I get older the picture of what my skin wears is starting to solidify. It hasn’t changed at all for two years.

I am looking forward to filling in this mural on myself, with the help of my tattoo artist. I will get to wear the visual song-story of myself where others can see, and this is so exciting.

Tattoo and aging

Sometimes I think about what will happen if I am covered in sleeves and begin to wish for my arms to be unadorned. Will I miss being able to wear sleeveless dresses and present an air of sophisticated cocktail elegance, especially as an older woman? Will this affect my career professionally, if people see animals curled around my lower arms while I’m trying to talk like I’m a serious person.

But then I think that isn’t me anyway. I can achieve cocktail elegance with tattoos if I want, and my career is sadly more likely to struggle because of my gender than whether I have cats tattooed on my arms. And I don’t (And won’t) let my gender stop me, so why would tattoos ever stop me?

I look at photos of older tattoos and I see a life lived in a skin the owner is happy in. And I can’t imagine anything more wonderful than that.